Author: Chakra Ip

Published on: Asia Democracy Chronicles

Date: 3 November 2022

Many of China’s rights lawyers are not backing down despite the growing challenges to their cause.

On Sept. 15, 2022, at a subway station in Beijing, police suddenly approached prominent human rights lawyer Wang Quanzhang and his wife, Li Wenzu, and escorted them home. Wang had spent five years in prison and was released in 2020; he is still practicing law. According to the police, they took him and his wife home as the U.S. Constitutional Day was approaching and they were not allowed to go anywhere during this sensitive period.

That line of reasoning sounds ludicrous. Why should Wang and Li be deprived of their freedom of movement just because of a milestone date of another country? But this took place in China, where rights lawyers and advocates are placed under constant surveillance and have their freedom of movement restricted, especially before sensitive anniversaries and congresses.

Just a few weeks before Wang and his wife were forced to return home, police called lawyer Yu Wensheng and his friends and told them to cancel a planned meeting. Yu was released from prison in March 2022 after spending four years behind bars for “inciting the subversion of state power.” The police said that he and his friends could not meet up because U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi was then visiting Taiwan.

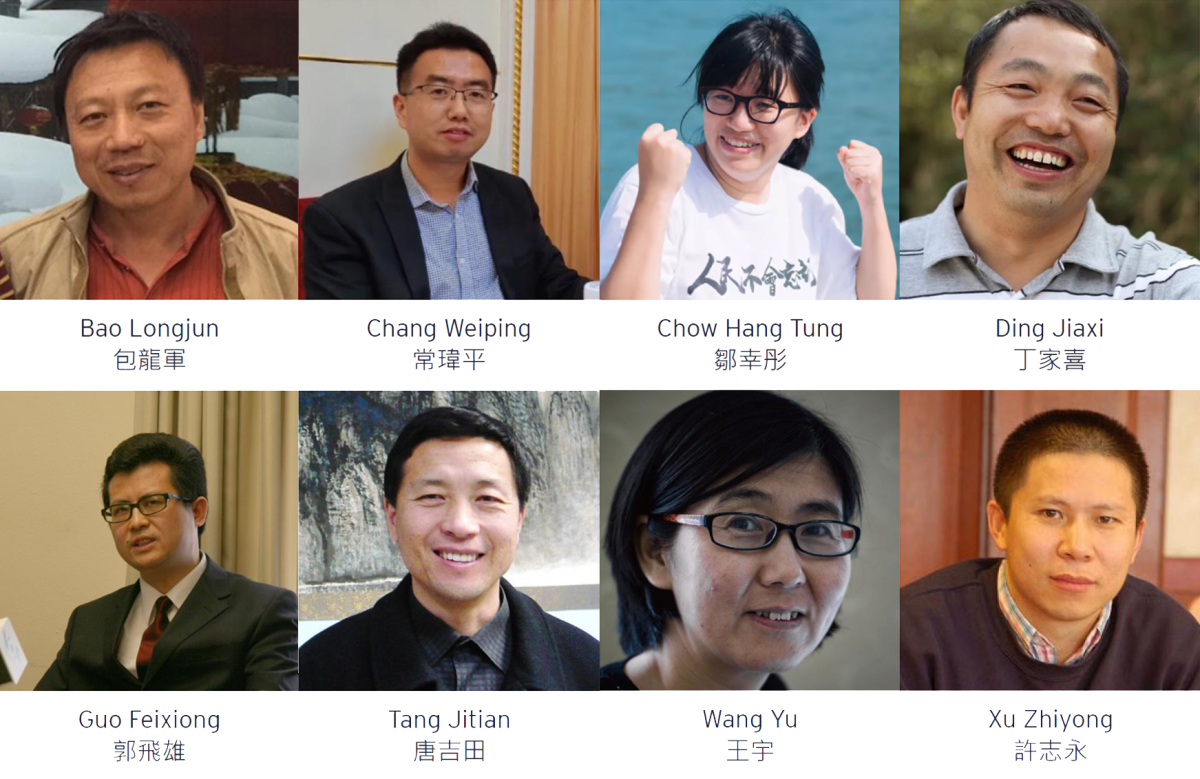

These photos show some of the over 300 Chinese lawyers and legal advocates that have been detained by the state since it began a massive crackdown on July 9, 2015. Many more continue to be arrested and imprisoned while the whereabouts of others remain unknown. (Photos: The 29 Principles)

Since the 2000s, human rights lawyers have been gaining prominence in China as legal education expanded and legal reform allowed lawyers to represent their clients even during investigations, not just in court. Lawyers have played a vital role in defending human rights in China over the past two decades. But they have been under increasing pressure from the authorities even as civil society in China has been shrinking.

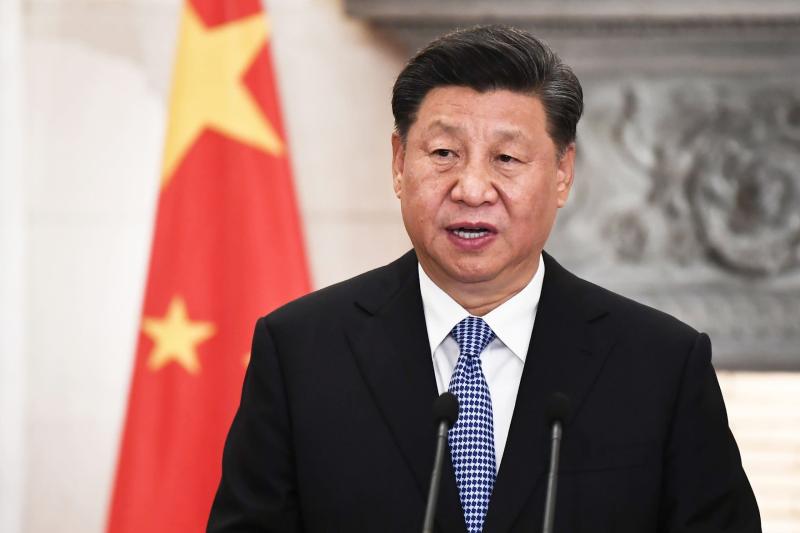

This year, the state’s grip on rights lawyers and other perceived dissidents tightened even more, particularly in the run-up to the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party. Held last Oct. 16 to 22, the Congress was the most important event in China’s political system and saw President Xi Jinping extending his reign into an unprecedented third term. Notably, most rights advocates and petitioners were placed under surveillance by the authorities beforehand. Some may even have been taken away from their homes to wait out the end of the event elsewhere.

Yet even though they are constantly facing all kinds of suppression, rights lawyers in China remain determined to safeguard human rights and freedoms. Even those who have spent time in jail go back to being active, joining their colleagues in helping the vulnerable across the country, providing legal advice, and representing the victims in public-interest cases.

From court to calling out authorities

China’s rights lawyers have been eager to help minorities and disadvantaged groups defend their rights. Although they often face a risk of reprisal from the authorities, they have not shied away from taking on sensitive cases such as those of Falun Gong or political dissidents.

Rights lawyers, however, have not only provided professional advice or represented victims in abuse cases. They are also often present and play a vital role in speaking out in the midst of scandals involving those in power. These have included the Taishi village incident in Guangdong in 2005, in which hundreds of villagers protested in demand of the removal of the village chief involved in corruption; and the Chinese milk scandal in 2008, in which six children died and more than 300,000 people were affected after drinking melamine-tainted milk.

Moreover, after experiencing miscarriages of justice and corruption in government, some of them have become strong critics of the government, calling for political and legal reforms and advocating for democracy in China. For these lawyers, it is impossible to defend people’s rights if the political and legal systems did not respect human rights.

But their appeals have not been tolerated by the Chinese authoritarian regime, which regards any suggestion to change the one-party system as a subversion of state power. Not surprisingly, rights lawyers now seem to be among the key targets of authorities. Some have had their licenses revoked or have been detained by the police.

Gao Zhisheng was among the first group of lawyers who faced suppression beginning in the 2000s. Since 2006, Gao — perhaps the most famous rights lawyer in China — has been detained and subjected to torture and ill-treatment on several occasions, causing him severe mental and physical injuries. He was placed under house arrest in 2014, after serving a jail sentence on charges of “inciting subversion of state power.” In August 2017, however, he was forcibly disappeared again; his whereabouts remain unknown.

Suppression intensifies in the Xi era

In July 2012, before the 18th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, a front-page article in the overseas version of the state-owned People’s Daily labeled human rights lawyers as among the forces used by the United States to interrupt China’s rise in the international stage. In China, the government usually drops subtle hints about its policy changes in the state media; the article was regarded as a prelude to a harsher and more brutal suppression of rights lawyers and advocates.

This was the backdrop to the historic crackdown on human rights lawyers in 2015 (also known as “709 Crackdown”). Throughout that year, more than 300 activists, mainly lawyers, paralegals, and their family members, were detained or prevented from leaving the country. Some were charged with subversion and sentenced to prison, including lawyer Zhou Shifeng, director of the Fengrui law firm — labeled by the government as a backstage manipulator inciting social disturbance. Zhou was released in Sept. 2022 and returned to his home, but it is believed that he has been placed under surveillance.

The vise-like grip on Chinese rights lawyers and other perceived dissidents tightened this year as the Chinese Communist Party held its National Congress in October 2022. Rights advocates brace for a long road ahead as Xi Jinping extends his presidency to an unprecedented third term. (Photo: Shag 7799/Shutterstock.com)

By conducting a mass arrest of human rights lawyers across the country, the authorities aimed to silence all lawyers and eliminate them from civil society. Yet while Beijing dealt a devastating blow to rights lawyers, many kept on with the fight. Some lawyers still chose to come forward and help their beleaguered peers. For example, Yu Wensheng stepped up to represent Wang Quanzhang who was charged with subversion; Li Yuhan, a veteran rights lawyer in China, took on the case of Wang Yu, the first lawyer arrested in the crackdown.

Citizens of China have since faced a more oppressive environment than ever, with tighter social control, such as the increasing number of surveillance cameras on streets, intensified censorship on the internet and social media, and more frequent harassment from the police. With the Chinese government putting “stability maintenance” as its priority and tightening its grip on political dissidents, China’s public safety spending reached US$210 billion in 2020 — double the figure 10 years prior, according to Nikkei Asia. The sum is also seven percent more than its national defense spending.

No giving up

Despite mounting political risks, human rights lawyers have pressed on. In 2020, rights lawyers including Lu Siwei, Ren Quanniu, Liang Xiaojun, and Lin Qilei took on the cases of 12 Hong Kong activists who were arrested while trying to flee to Taiwan by boat. The activists were sent to a prison in the southeastern province of Guangdong. Their lawyers had their licenses either revoked or suspended. In fact, The 29 Principles and other rights groups have documented that from 2017 to 2021 alone, around 40 lawyers in China have had their licenses revoked or suspended after handling human rights cases, in contrast to 12 cases from 2012 to 2016.

Source: The 29 Principles, Freedom House

Jail time remains an ever-present risk for lawyers and anyone fighting for rights in China. Yu Wensheng, for instance, was sentenced to four years in prison in 2020. Yu, who had a chance to leave China after the 709 Crackdown but decided to stay, was known for talking about “sensitive” issues with the foreign press. In 2018, he wrote an article calling for constitutional reform. Shortly after a local publication ran it, he was arrested. Yu was finally released from Nanjing prison last March.

Wang Yu’s lawyer Li Yuhan, meanwhile, has been detained since Oct. 2017. She finally stood trial in October last year for “fraud” and “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” Yet up to now, no verdict or sentence has been made public regarding her case. The health of the 73-year-old, who has a heart condition, has significantly deteriorated while in detention.

In Dec. 2019, several rights lawyers and activists were arrested by police after attending a private gathering in the southeastern city of Xiamen, at which they discussed political issues and public affairs. Among those taken away by the police, legal scholar Xu Zhiyong and lawyers Ding Jiaxi and Chang Weiping were charged with subversion and have been detained ever since. During their detention, Xu, Ding, and Chang have been subjected to torture, including sleep deprivation, being shackled to a “tiger bench” during interrogation (a form of torture commonly used by Chinese police that inflicts extreme pain), and insufficient food. Their cases were finally tried in the summer of this year, but no verdict has been given as of writing.

The last two decades or so have seen China develop into one of the world’s top economies. It now has a growing global influence. Yet, China has fallen short of the world’s naive expectation that an improvement in economic growth would be accompanied by an improvement in its human rights record. What Chinese rights lawyers have experienced in the past 20 years is emblematic of the decline of human rights in China, with many in despair over the country’s future. But looking at how lawyers have relentlessly challenged the authorities regardless of retaliation, we can only have hope that one day their efforts will pay off.