In carrying out duties as a human rights lawyer in China, one can expect to have your lawyer’s license revoked; be stalked, harassed and illegally detained; face torture, imprisonment and separation from one’s family. Yet, the most horrifying fate is called “enforced disappearance”.

According to the United Nations, an enforced disappearance occurs when: "persons are arrested, detained or abducted against their will or otherwise deprived of their liberty by officials of different branches or levels of Government, or by organised groups or private individuals acting on behalf of, or with the support, direct or indirect, consent or acquiescence of the Government, followed by a refusal to disclose the fate or whereabouts of the persons concerned or a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of their liberty, which places such persons outside the protection of the law.” To combat this problem, the UN General Assembly adopted the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance. At the time of writing, 98 countries have signed the Convention. China, the world's most populous country and a permanent member of the UN Security Council, not only refuses to sign the Convention, but continues to use "enforced disappearance" against human rights lawyers and legal scholars. The victims are subjected to secret interrogation, detention and even torture, without means to inform their families and lawyers. Their rights to life, health, fair trial and judicial protection are severely violated.

In some cases of “enforced disappearance”, lawyers are suddenly “arrested” by the authorities, even after a prolonged period of disappearance. Lawyer Wang Quanzhang disappeared in July 2015 and, after repeated inquiries were made by his family and civil society about his whereabouts, authorities issued an arrest warrant in early 2016 confirming the place and reason for his detention.

Occasional cases of these disappearances gain prominence either nationally or internationally, but when that person finally reappears, they often remain silent about what has happened during their disappearance, suggesting they have been pressured not to talk about their experience, as in the case of Lawyer Tang Jitian. In addition to the suffering of the victim, their family suffers the whole time, not knowing the victim’s whereabouts for many years and without knowing if he is still alive.

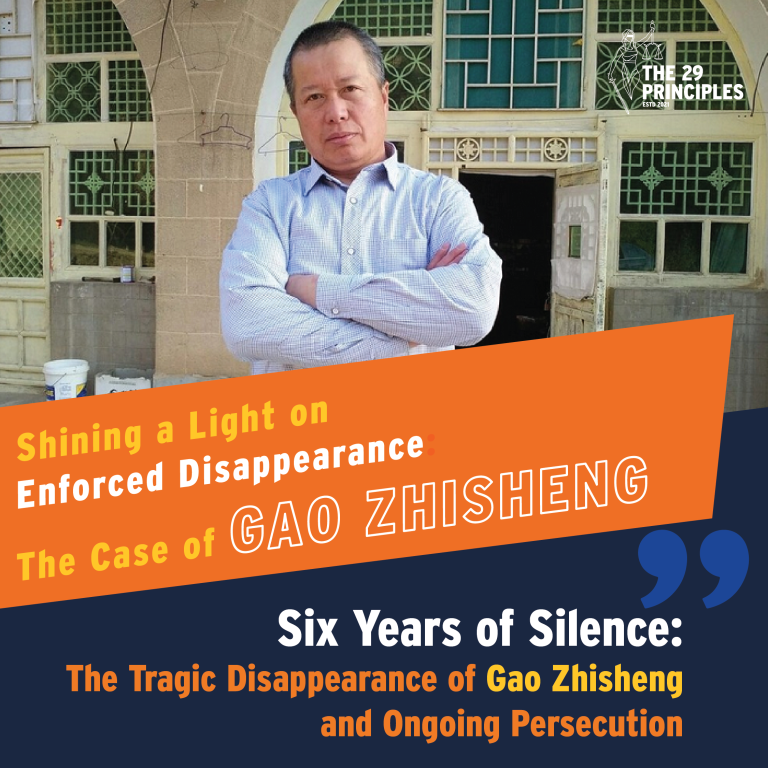

Lawyer Gao Zhisheng, who disappeared on 13 August 2017, belongs to this category and his family has been living in a nightmare for over six years.

From “Top Ten Lawyers in China” to Human Rights Lawyer

Gao Zhisheng, born in 1964, came from Jia County, Yulin City of Shaanxi Province. His father passed away early in Gao’s life and left many children behind. As a child, Gao had to collect herbs to sell and worked as a coal miner to support his family. Despite such hardship, he studied in his spare time and finally became a lawyer at the age of 31. He has described how during the first two years of his practice (1996-8) in Urumqi, Xinjiang, he had no connections and no resources to get clients. He mainly represented the vulnerable groups for free, saying “Out of 40 cases, 30 of them were free of charge...I don’t see these free cases as the capital for making myself famous in future...I was born in poverty and I know the feelings of poor people, so I know what I want to do... but helping others should not be an act of charity. I am looking into the future, I want to use this life to save my next life!”

His dedication to vulnerable groups earned him widespread recognition and won over more clients. In 2000, he moved from Xinjiang to Beijing, founded his own law firm “Sheng Zhi Law Firm”, which employed 20 lawyers. He was celebrated as one of the "Top Ten Lawyers in China" by the Ministry of Justice of China. At the same time, he made a pledge to maintain that "one-third of the cases [he takes on] are for the poor and disadvantaged, free of charge.”

Many years of representation of vulnerable groups made Gao an enemy of local governments and many well-known enterprises. He investigated and reported on the forced expropriation of private oil fields in northern Shaanxi province, the so-called the first case of private enterprises defending their rights in 2003. His book revealed how the local government lured as many as 60,000 people to sign contracts, investing RMB 7 billion to develop the oilfield and then used administrative orders to deprive the people of their investment; he drew attention to the embezzlement, coercion, and detention the investors faced and how they were, in the end, forced to flee from repression.

In 2005, Gao’s assistant Yang Maodong (a.k.a. Guo Feixiong) travelled to Taishi Village, Panyu District of Guangzhou City to provide legal advice for villagers who were seeking to remove their village chief accused of corruption. Yang reported the progress of the case on his blog and attracted international attention. The central government was disturbed by the news and instructed Guangdong provincial government to investigate thoroughly. As a result, Yang has since been subjected to physical assaults, repressions and prolonged imprisonment.

As a Christian, Gao represented Pastor Cai Zhuohua, who was charged with "illegal business operations" and sentenced to three years in prison in 2005, for printing and giving free Bibles to other Christians. In China, religious publications must be approved by the State Bureau of Religious Affairs, which allows only a limited number of Bibles and other religious books to be printed each year and only to be sold in state churches. As more and more people convert to Christianity in China, these restrictions fail to meet the needs of the public. It is commonly believed that authorities are using charges of economic crimes as a cover to restrict freedom of religious belief.

In mid-1999, China’s Ministry of Civil Affairs issued a decision banning the Research Society of Falun Dafa and the Falun Gong organisation under its control after judging them to be illegal. Over the past 20 years, a full scale crackdown has been carried out against about 70 million Falun Gong practitioners. From December 2004 to December 2005, Gao wrote four open letters to the then National People's Congress and state leaders Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao exposing the authorities' arbitrary arrests of Falun Gong practitioners, their systematic torture and the related human rights and constitutional violations. In his letters, he urged the authorities to end the persecution of Falun Gong practitioners and investigate allegations of human rights abuses.

Honour and Prosecution

Gao is widely respected for his outspokenness for the vulnerable and has gained international recognition. In 2007, the American Board of Trial Advocates selected Gao to receive their prestigious “Courageous Advocacy Award”; in 2010, he won the "International Human Rights Lawyer Award" from the American Bar Association. Lawyer Teng Biao called him not “one of” the bravest lawyers in China, but indisputably “the” bravest one. Inspired by him, Lawyer Albert Ho in Hong Kong launched a weekly 24-hour hunger strike in 2006 which continued for years after; and founded the China Human Rights Lawyers Concern Group in early 2007, to lobby legal professionals in Hong Kong to support their counterparts in China.

Yet in China, his name "Gao Zhisheng" has been listed as a sensitive word and cannot be searched on internet. Starting from October 2005, about 20 plainclothes officers from the Beijing State Security Bureau and Public Security Bureau have followed him and his family, with more than ten vehicles monitoring his flat on daily basis. In August 2006, Gao’s lawyer’s license was revoked and he was kidnapped and tortured.

After this, on 22 December 2006, Gao Zhisheng was sentenced to three years in prison, suspended for five years, for the crime of "inciting subversion of state power” in Beijing. However, even during his suspension, he was repeatedly kidnapped and put under torture.

However, he did not stop speaking out for the vulnerable. In 2007, Gao Zhisheng published an "Open Letter to the U.S. Congress" describing the human rights situation in China and calling on the USA to boycott the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. As a result, he was taken away by the authorities and tortured for nearly two months. In February 2009, Gao Zhisheng again lost contact with the outside world for nearly two years. This drew international attention, with pressure resulting in an appearance in Beijing in April 2010 where he was interviewed by the Associated Press briefly, before he went missing again for another 20 months. The Associated Press revealed that Gao Zhisheng was subjected to long-term and severe torture throughout his disappearance.

The official Xinhua News Agency reported in 2011 that Gao Zhisheng had repeatedly violated the regulations of his suspended sentence, leading to the court revoking his suspended sentence and ruling that he must serve the remaining three years in prison. After Gao was released in 2014, the authorities continued to place him under house arrest. At that time, his physical and mental health were severely damaged with many of his teeth coming loose.

Gao was last seen in August 2017. Since then his whereabouts have remained unknown. It is believed that his enforced disappearance is related to the fact that he had smuggled a book detailing his decade-long torture out of China to be published overseas.

Long years of surveillance, their children being refused admittance to schools in Beijing and their daughter’s suicidal thoughts, forced Mrs Gao, Geng He, to flee China with their 16-year-old daughter and 5-year-old son. They illegally crossed the border to Thailand in January 2009 and later applied for political asylum in the USA. Like many family members of human rights lawyers, leaving China means that they might never again see their husbands and fathers who stay in China.

Open-ended “Enforced Disappearance”

Between 2014 until shortly before his disappearance in 2017, Geng He could sometimes call Gao Zhisheng to ask about his situation. Geng He recalled their last phone call: "I can't remember exactly what we talked about because it seemed like just another call but, of course, I asked him how he was," she said. "His mood was good. He said he was fine. That was what he was like; always confident and positive.” A few days later, when she called again, no one answered. Since then, she has never heard from her husband again. She hired a lawyer in Beijing to help her search for Gao, but no one was willing to tell them anything.

"Enforced disappearance" is a tactic adopted by the authorities to spread fear in society, to silence the disappeared, threaten their loved ones and intimidate their supporters. Two relatives of Gao Zhisheng have ended their lives for reasons related to Gao: his elder sister, who cared about Gao deeply, witnessed Gao's first arrest and subsequently suffered from insomnia and depression. In May 2020, out of despair, she committed suicide by jumping into a river in Shandong. In 2015, Mrs. Gao’s brother-in-law had his identity card confiscated by the police because of his connection to Gao Zhisheng and had to report at the police station regularly. Later, when he was suffering from cancer and needed an identity card to buy medicine, the police refused to return it. Unable to bear such pain, he committed suicide by jumping off a tall building.

According to Geng He, the public security bureau in Yulin, Shaanxi Province finally confirmed that Gao Zhisheng was in its hands in early April 2021, but it would not allow them to meet or talk to each other. Geng He is deeply suspicious, imagining the worst outcome: "My greatest fear is that the Communist Party will use Covid-19 as an excuse to make him disappear forever." She made a plea to the Chinese government to allow the world to “see him if he’s alive or see his corpse if he’s dead”. She demanded the Chinese government to return Gao’s ashes if he is dead, or if he is alive, she has told the government, “I have raised two children to adulthood and am willing to return to China to join my husband in jail. I demand the Chinese embassy to issue a visa for me to enter China in accordance with the Sino-US consular agreement.” However, two years have passed and the Chinese authorities still turn a deaf ear to her request.

Article 183: Where the whereabouts of a citizen has been unknown for two years, and an interested party applies for declaration of the citizen to be missing, the application shall be filed with the basic people's court of the place where the missing person is domiciled...

Article 184: Where the whereabouts of a citizen has been unknown for four years...if an interested party applies for declaration of the citizen to be dead, the application shall be filed with the basic people's court of the place where the missing citizen is domiciled...

Article 185 After accepting a case concerning the declaration of a citizen as missing or dead, a people's court shall issue a public notice in search of the citizen whose whereabouts is unknown. The period for the notice of declaration of a person as missing shall be three months, and the period for the notice of declaration of a person as dead shall be one year...Upon the expiration of the time limit of the public notice, the people's court shall, depending on whether the facts about the disappearance or death of the person have been confirmed, make a judgment declaring the person missing or dead or make a judgment to reject the application for such a declaration.

China’s Civil Procedure Law (2017)

Whether it is based on international conventions, humanitarian reasons, or China's own laws, the Chinese authorities are required to inform the family about Gao’s whereabouts and conditions. Yet the Chinese government continues to ignore these responsibilities and international calls to ratify the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances. Neither does it accept a decade-long request from the United Nations Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances to visit the country. Instead it keeps adopting "enforced disappearance" to silent dissidents and human rights lawyers.